- Anesthesiology Malpractice

- Posts

- Post Extubation Pediatric Code - Tonsillectomy

Post Extubation Pediatric Code - Tonsillectomy

Case #23

A 16-year-old boy was booked for a tonsillectomy and uvulopalatopharyngoplasty at a surgery center.

He was 5’9” and 215lbs, and suffered chronic tonsillitis and sleep apnea.

He had an eventful emergence at the end of the case.

Become a better anesthesiologist by reviewing malpractice cases.

Paying subscribers get a new case every week and access to the entire archive.

After observing the patient for a few minutes and getting ready to leave the room, he suddenly began coughing.

After a call for help, another anesthesiologist arrives and ENT returns to the OR.

The patient was reintubated and moved back to the OR table.

The surgeon began packing the bleeding site.

Monitors were reapplied.

ACLS was started and after several minutes of resuscitation vfib was shocked back into a perfusing rhythm.

The patient was transferred to the hospital and unfortunately suffered permanent debilitating injuries, now requiring long term care.

The family sued the surgeon, anesthesiologist, and 2nd anesthesiologist who came to help.

An expert for the plaintiff wrote the following opinion.

The lawyer for the 2nd anesthesiologist argued his client should be dismissed as he was not involved in any pre op or intra op care, and assisted only in the emergent setting, mostly as a recorder.

Join thousands of anesthesiologists on the email list.

Expand your medicolegal expertise.

CME credit available with the purchase of a CME subscription.

Outcome

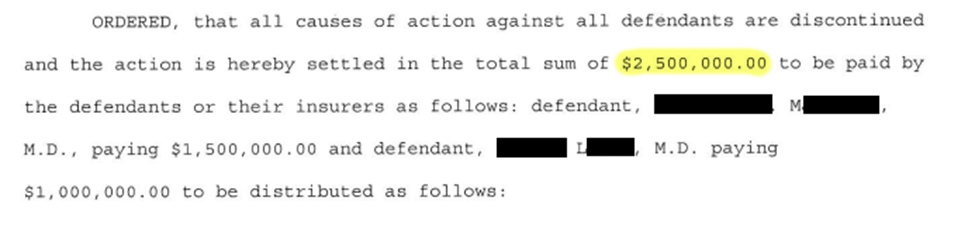

The case settled before trial.

The ENT paid $1.5 million.

The anesthesiologist paid $1 million.

The 2nd anesthesiologist who arrived to help was dismissed.

MedMalReviewer/Anesthesiologist Analysis:

There was some finger pointing in this case but far from the worst I’ve seen. The ENT was adamant tonsillar bleeding does not cause cardiac arrest and consistently referred to the bleeding as “oozing” only. The anesthesiologist claims extubation was uneventful, and bleeding (1L total!) precipitated the coughing, not the other way around. In the end, they both shared the liability.

I could not get a good timeline for how quickly the patient was reintubated, or when monitors were applied and asystole recognized. The only anesthesia related opinion in the court records did not touch on this. It is directed against the 2nd anesthesiologist/medical director who arrived to help. I will say if you are going to give a deposition regarding a cardiac arrest case, and you are medical director of the ASC (as this anesthesiologist was), it should be obvious what they will ask you. There shouldn’t be any surprises you need to know your ASC’s protocols and of course ACLS down cold. This anesthesiologist struggled through his deposition and gave inaccurate answers about a topic he should be an expert on. It may be a nervous experience to give a deposition, but a review of the materials and brushing up on relevant medical topics should be a given.

The biggest cornerstones of cardiac arrest care are high quality chest compressions that minimize interruptions, and early defibrillation (if applicable). If this patient did not received high quality compressions, the care may have been below the standard of care, although proving that poor compressions caused his bad outcome is questionable. ACLS represents the most simple and basic aspects of cardiac arrest resuscitation, not high level care. Advanced resuscitation often includes interventions that go beyond what is included in an ACLS class. It’s fine to reference ACLS, but it does not define the standard of care for physicians who should be resuscitation experts.

Long term care costs are always going to be high, especially in a pediatric patient. This is where we see large settlements and verdicts. These numbers are likely policy limits or close to it.

Reply